Chinese mourners are using AI to digitally resurrect the dead

NewsFeed A growing number of Chinese mourners are using AI to help them cope with their grief by generating digital replicas of their loved ones. Published On 27 Dec 202327 Dec 2023 Adblock test (Why?)

Who are the Israeli refuseniks picking jail over the Gaza war?

He’s a baby-faced 18-year-old with a heart full of idealism. When Tel Aviv teen Tal Mitnick refused to enlist in the Israeli army, he was put on trial: on Tuesday, he was taken to military prison to serve a 30-day sentence. Standing alone in a country on a determined war footing is an agonising decision. But, speaking at Tel Hashomer, a base near the Gaza fence in central Israel, Mitnick staunchly defended his decision. “I believe that slaughter cannot solve slaughter,” he said. “The criminal attack on Gaza won’t solve the atrocious slaughter that Hamas executed. Violence won’t solve violence. And that is why I refuse.” Tal Mitnick, an activist in the Mesarvot network showed up today at Tel Hashomer base and was sentenced to 30 days in military prison. Listen to what he had to say before he walked in. Support him and other refusniks: https://t.co/drRtLjk4U3 pic.twitter.com/zu1XZJqmhG — Mesarvot מסרבות (@Mesarvot_) December 26, 2023 The statement appeared on the X account of Mesarvot, a support network connecting refuseniks in a campaign against the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories. In an earlier interview posted on the account, Mitnick laid out his universalist stance on the conflict. The solution, he said, would not come from corrupt politicians in Israel or from Hamas. “It will come from us, the sons and daughters of the two nations,” he said. Friends came out in support of Mitnick, holding placards with phrases like: “You cannot build heaven with blood”, “An eye for an eye and we all go blind” and “There is no military solution.” Military service is mandatory for most Jewish Israelis, viewed as a rite of passage. In the country’s highly militarised society, so-called refuseniks risk being labelled traitors. Are refuseniks common? No. Generally speaking, refuseniks may end up serving repeated prison services, ordered to return to recruitment centres again and again. Some wind up doing months behind bars before they are eventually discharged. The Israeli military does have a conscientious objectors committee, but exemptions are usually only granted on religious grounds – the ultra-Orthodox Haredi Jews, for instance, are legally exempt. Refusing to serve as a matter of political principle is not considered a valid objection. An ultra-Orthodox Jewish man walks behind Israeli soldiers at the entrance to a military recruiting office in Jerusalem on July 4, 2012. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s largest coalition partner had issued a veiled threat to quit the government over a dispute on amending Israel’s compulsory draft policy, which grants exemptions to ultra-Orthodox men studying the Torah in religious colleges [File: Baz Ratner/Reuters] Earlier this year, Amnesty International released a report on Yuval Dag, a 20-year-old who had made his political objections clear before his summons. The army classified his refusal as disobedience and sentenced him to 20 days at Neve Tzedek military prison in Tel Aviv. The rights group named four other individuals – Einat Gerlitz, Nave Shabtay Levin, Evyatar Moshe Rubin and Shahar Schwartz – who were repeatedly detained in 2022. Conscientious objectors commonly serve five months or more in prison – a high price to pay for young people doing what they believe to be right. Many objectors come to their decision after participating in protest movements, whether on LGBTQ rights, climate change or Israel’s occupation, violence and discrimination against Palestinians — a system that many rights groups have compared with apartheid. Are there any famous refuseniks? In 2003, a group of Israeli Air Force pilots provoked national fury when they refused to take part in operations in the West Bank and Gaza. Submitting a letter to the media, they branded attacks on the territories as “illegal and immoral”. The case was noteworthy, involving elite army members like Brigadier General Yiftah Spector, considered a legend in the forces for his attack on Iraq’s nuclear reactor in 1982. The government accused the pilots of “pretentious snivelling”. That same year, the country’s elite commandoes also defied orders to carry out attacks on the occupied territories. Setting out their position in a letter, 15 reservists from the Sayeret Matkal unit, often compared with the British army’s SAS, said: “We will no longer corrupt the stamp of humanity in us through carrying out the missions of an occupation army. “In the past, we fought for a justified cause (but today), we have reached the boundary of oppressing another people.” In 2007, swimwear model Bar Refaeli married a friend to avoid military service, later telling the press that “celebrities have other needs”. Later, to avoid damage to the companies she worked for, she agreed to participate in an enlistment campaign. The case ignited a debate on how easy it is to dodge conscription. Hang on, wasn’t there dissent in army ranks this year? Yes, but it was not linked to the occupation. In early March, about 700 reservist soldiers – including some top brass – resigned en masse during widespread protests over Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s judicial overhaul. Critics accused him of curtailing Supreme Court powers to shield himself from corruption charges. People take part in a demonstration against Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his nationalist coalition government’s judicial overhaul, in Tel Aviv, Israel, on July 22, 2023 [File: Corinna Kern/Reuters] Explaining his refusal to serve in the army, Dag said that reservists had resigned because they were afraid of living in a dictatorship. But, he pointed out, “We need to remember that in the occupied territories there has never been democracy. And the anti-democratic institution that rules there is the army.” Responding to rebellion in the ranks, Netanyahu said: “There’s no room for refusals.” Military service was, he said, “the first and most important foundation of our existence in our land …The refusals threaten the foundation of our existence.” Netantahu’s view is not unusual. Across the political spectrum, with the exception of some left-wing and Arab groups, parties condemn the refusal to serve for a number of reasons. Left wingers worry about polarisation, claiming that refusing to serve will encourage right-wing resistance to removing settlements. Right wingers

Russia accuses US of threatening global energy security

Russia has claimed that US sanctions levied against the Arctic LNG 2 project undermine global energy security. The Russian foreign ministry’s spokeswoman hit out on Wednesday at Washington’s “unacceptable” move to clamp down on the massive Arctic LNG 2. The sanctions are just the latest measure implemented as the West seeks to limit Moscow’s financial ability to wage war in Ukraine. The remarks came after Washington announced sanctions against the new liquefied natural gas plant that is under development on the Gydan Peninsula in the Arctic last month. “We consider such actions unacceptable, especially in relation to such large international commercial projects as Arctic LNG 2, which affect the energy balance of many states,” said foreign ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova. “The situation around Arctic LNG 2 once again confirms the destructive role for global economic security played by Washington, which speaks of the need to maintain this security but in fact, by pursuing its own selfish interests, tries to oust competitors and destroy global energy security.” Russia is the fourth-largest producer of sea-borne LNG behind the United States, Qatar and Australia. The Arctic LNG 2 project is a key element in Russia’s efforts to boost its share of the global market to a fifth by 2030-2035 from 8 percent now. However, the sanctions saw partners from China, Japan and France who hold a combined 40 percent of the project suspend participation last week. Project developer Novatek was also forced to declare force majeure over LNG supplies from the project, which was slated to start production in early 2024. Western countries, seeking to cripple Moscow’s military might, have imposed wide-ranging sanctions against Russian firms and individuals following the Kremlin’s decision to send tens of thousands of troops into Ukraine in February last year. However, Russia insists that Europe has been hit harder by the sanctions due to raised energy prices, while it has been successful in swiftly finding new markets in Asia. Almost all of Russia’s oil exports this year have been shipped to China and India, Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak said on Wednesday. Wave of drones Russia hopes that the income from Asian energy customers can continue to help drive its invasion, as it eyes Ukraine’s struggle to access funds and weapons from Western partners. On Wednesday, Ukrainian authorities said two people were killed after Russian forces sent a wave of attack drones against the country in an overnight raid. The Ukrainian air force said that 32 of 46 Iranian-made drones deployed by Russia had been shot down. The air force said the military had destroyed drones over parts of central, southern and western Ukraine. Most of those that got through defences struck near the front line, mainly in the southern Kherson region. Oleh Kiper, the governor of Ukraine’s Odesa region, said that a 35-year-old man was killed by debris from a downed drone in a residential area. Another man died in the hospital from his injuries. Four others, including a 17-year-old boy, were injured, according to Kiper. More than 10,000 civilians have been killed in Ukraine since Russia’s full-scale invasion, with about half of recent deaths occurring far behind the front lines, according to the UN Human Rights Office. Adblock test (Why?)

InstaAstro: Pioneering Quality Astrology Guidance With Broad Audience Appeal

InstaAstro is built on the principle of “Quality over Quantity”, a philosophy that distinguishes it in an industry often perceived as saturated with generic, mass-produced content.

Why is Bengaluru on the boil? Outlets face vandalism amid ‘60% Kannada’ order, malls forced to close

Karnataka Rakshna Vedikehad set a December 27 deadline for all establishments to implement 60 per cent Kannada in signboards across the city.

IOA forms 3-member ad hoc committee to run affairs of suspended WFI

The Sports Ministry on Sunday suspended the WFI, three days after it elected new office bearers with Brij Bhushan Singh loyalist Sanjay Singh as president.

‘Switch to defence’: Ukraine faces difficult 2024 amid aid, arms setbacks

Kyiv, Ukraine – Whenever Svitlana Matvienko hears the wailing of air raid sirens, she goes down to the nearby subterranean shopping mall. There, a barista she’s on a first-name basis with gets her a large latte, and Matvienko clacks away on her tiny silver laptop, sitting next to several dozen others waiting out the air raid. “I’m like a little Pavlov dog, but the sirens make me drool for coffee,” the 52-year-old freelance marketing expert told Al Jazeera with a sense of self-deprecating humour that helps Ukrainians cope with the war. The crowd around her is minuscule in comparison with last year, when hundreds of people thronged the same Metrograd mall, often staying for the night with their weeping children and squealing pets. To Matvienko, the December 15 air raid was yet another multimillion-dollar exercise in the futility of Russia’s war effort, with all the cruise missiles and kamikaze drones shot down and no casualties reported. And when asked about what awaits her and all of Ukraine in 2024, the ginger-haired, petite mother of two pointed up, as if her manicured forefinger could pierce the ceiling towards the grey sky and howling sirens, and said: “A lot more of this.” This year has been uneasy and somewhat disappointing to many Ukrainians. The long-awaited counteroffensive in eastern and southern regions stalled as Russian bombardment of urban centres resumed to sow panic and destroy power stations and central heating facilities. “Because the summer counteroffensive lacked notable results, Ukrainians got back to feeling danger and threat that seemed to have subdued as they were getting used to the ongoing war,” Svitlana Chunikhina, vice president of the Association of Political Psychologists, a group in Kyiv, told Al Jazeera. “We need to adapt to the war again, to correct expectations and life strategies taking into account more realistic estimates,” she said. The counteroffensive’s fiasco seems sobering in comparison with last year’s emotional rollercoaster, when Russian troops horrified Ukraine by advancing from three directions – only to withdraw from around Kyiv and northern regions and to suffer a string of humiliating defeats in the east and south. This winter, the tables seem to have turned. “Now is the time to switch to defence” along the crescent-shaped front line that traverses eastern and southern Ukraine for more than 1,000km (600 miles), says Kyiv-based analyst Igar Tyshkevich. “For the winter campaign, Ukraine’s logic is to hold the front. Hold the Black Sea, keep the ports open, work the political field to guarantee the reception of military aid as the spring approaches,” he told Al Jazeera. Kyiv’s manpower and arsenals are too depleted to go on the offensive next year, according to some top Ukrainian military experts. “We don’t have the resources for next year’s operation,” Lieutenant General Ihor Romanenko, the former deputy chief of the General Staff of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, told Al Jazeera. Polls show that the number of Ukrainians who believe that the war should go on until Ukraine regains all lost territories, including the Crimean peninsula that Russia annexed in 2014, is going down, albeit insignificantly. Sixty percent believe in Kyiv’s imminent military triumph, as opposed to 70 percent last year, according to a Gallup poll released in October. And almost a third of those polled – 31 percent – think that peace talks with Russia should begin “as soon as possible,” compared with 26 percent last year, the poll said. Most of the supporters of immediate negotiations come from southern (41 percent) and eastern (39 percent) Ukraine, where most of the hostilities took place this year, the poll said. Meanwhile, Israel’s war on Gaza has eclipsed the Russia-Ukraine war in the Western media and halls of power as aid to Ukraine has dwindled or been suspended. The aid has been keeping Kyiv afloat since the war began in February 2022 – and will be the key factor shaping the future and stability of Ukraine’s economy, according to Kyiv-based analyst Aleksey Kusch. “In theory, Ukraine can hold on for between six months and a year on its own. But that will require the freezing of a string of budget articles,” he told Al Jazeera. Only by 2025 will Ukraine achieve a “factor of safety” if some refugees return and Kyiv gets sizable investments, he said. More than six million people left Ukraine last year, mostly to Poland and other Eastern European nations, and another eight million have been displaced within the France-sized nation. Another key contributor to the economic growth will be the unblocking of Ukrainian ports on the Black Sea and Azov Sea to fully resume the shipment of grain and steel, a scenario that will require Kyiv to continue to assault Russia’s navy, Kusch said. This year, Ukraine’s economy showed small signs of recovery after 2022’s freefall, when the gross domestic product shrank by a third. This year, the GDP will have grown by 2 percent – and may gain another 3.2 percent in 2024, the International Monetary Fund said in October. It said the “stronger than expected” growth in domestic demand reflected the adaptation to the invasion and reversed the prediction of a 3 percent shrinkage for 2023. Another source of cautious optimism is the prospect of Ukraine joining NATO and the European Union – something that would safeguard the country from Russia politically and economically. At a summit in July, NATO member states agreed to simplify Ukraine’s path to membership, although they did not say when it could join. And in mid-December, the European Union decided to open membership talks for Kyiv, despite Hungary’s objections over the “mistreatment” of ethnic Hungarians in western Ukraine. The overwhelming majority of Ukrainians believe that their nation would join NATO (69 percent) and the EU (73 percent) within a decade, the Gallup poll showed. In 2024, Ukraine is also not going to see a change of leadership. All political parties with a presence in the Verkhovna Rada, Ukraine’s lower house of parliament, agreed in mid-November to postpone the presidential and parliamentary votes until the war is over. They said that too many

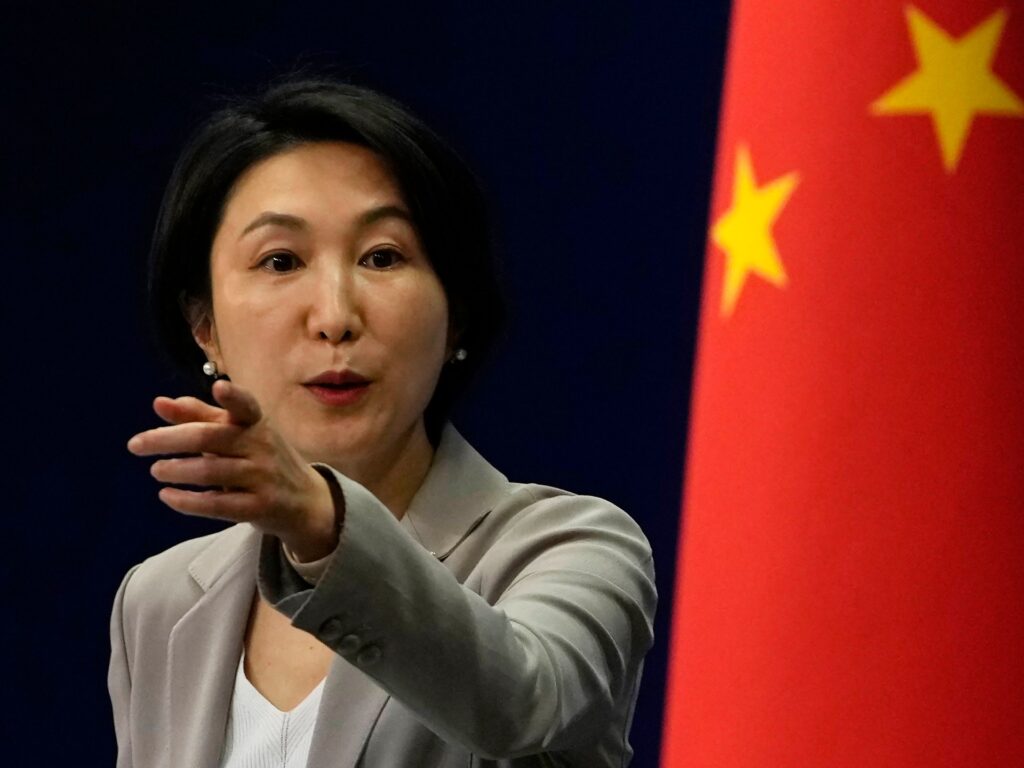

China sanctions US-based Xinjiang monitor

Los Angeles-based Kharon reported on human rights abuses committed against China’s Uighurs and other Muslim minorities. China has placed sanctions on a United States research company that monitors human rights in the northwestern region of Xinjiang. China announced late on Tuesday that Los Angeles-based research and data analytics firm Kharon and its two lead analysts are now barred from entry. The company has reported extensively on claims that Beijing is committing human rights abuses against Uighurs and other Muslim minority groups. Director of investigations Edmund Xu and Nicole Morgret, a human rights analyst affiliated with the Center for Advanced Defense Studies, were named as the two barred analysts in a statement published by Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Mao Ning. Any assets or property owned by the company or individuals in China will be frozen. Organisations and individuals in China are prohibited from conducting transactions or otherwise cooperating with them. The statement said that the sanctions were retaliation for Kharon’s contribution to a US government report on human rights in Xinjiang. Uighurs and other natives of the region share religious, linguistic and cultural links with the scattered peoples of Central Asia and have long resented the Chinese Communist Party’s heavy-handed control and attempts to assimilate them with the majority Han ethnic group. In a paper published in June 2022, Morgret wrote: “The Chinese government is undertaking a concerted drive to industrialise the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR), which has led an increasing number of corporations to establish manufacturing operations there.” “This centrally-controlled industrial policy is a key tool in the government’s efforts to forcibly assimilate Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples through the institution of a coerced labor regime,” she added. Such reports draw from a wide range of sources including independent media, non-governmental organisations and groups that may receive commercial and governmental grants or other outside funding. Harsh conditions China has long denied allegations of human rights abuses in Xinjiang, saying the large-scale network of prison-like facilities through which hundreds of thousands of Muslim citizens have passed were intended only to rid them of violent, extremist tendencies and teach them job skills. Former inmates describe harsh conditions imposed without legal process and demands that they denounce their culture and sing the praises of President Xi Jinping and the Communist Party daily. China says the camps are all now closed, but many of their former inmates have reportedly been given lengthy prison sentences elsewhere. Access to the region by journalists, diplomats and others is tightly controlled, as is movement outside the region by Uighurs, Kazaks and other Muslim minorities. “By issuing the report, the United States once again spread false stories on Xinjiang and illegally sanctioned Chinese officials and companies citing so-called human rights issues,” Mao was quoted as saying. “If the United States refuses to change course, China will not flinch and will respond in kind,” Mao was quoted as telling reporters at an earlier news briefing. The US has imposed visa bans and a wide range of other sanctions on dozens of officials from China and the semi-autonomous city of Hong Kong, including the country’s former defence minister, who disappeared under circumstances China has yet to explain. China’s foreign minister also was replaced this year with no word on his fate, fuelling speculation that party leader and head of state for life Xi is carrying out a purge of officials suspected of collaborating with foreign governments or simply showing insufficient loyalty to China’s most authoritarian leader since Mao Zedong. It is not immediately clear what degree of connection Xu or Morgret, if any, they had with the US government. Adblock test (Why?)

Analysis: In the Red Sea, the US has no good options against the Houthis

Operation Prosperity Guardian (OPG), the United States Navy-led coalition of the willing intended to allow international shipping to continue navigating safely through the Red Sea, is set to activate within days. Including allies from Europe and the Middle East, as well as Canada and Australia, the operation has been snubbed by three important NATO countries, France, Italy and Spain. What is the exact task of OPG? The official line, “to secure safe passage for the commercial ships”, is too vague for any naval flag officer to feel comfortable getting into. Admirals want politicians to give them precise tasks and clear mandates needed to achieve the desired results. Defining the threat seems easy, for now: antiship missiles and drones of various types carrying explosive warheads have been targeting merchant ships on the way to and from the Suez Canal. All were fired from Yemen, by the Houthi group also known as Ansar Allah which now controls most of the country, including the longest section of its 450km-long Red Sea coast. All missiles were surface-launched, with warheads that can damage but hardly sink big cargo ships. The Houthis at first announced that they would target Israeli-owned ships, then expanded that to include all those using Israeli ports, ultimately to those trading with Israel. After several attacks where the Israeli connection appeared very distant or vague, it is prudent to assume that any ship could be targeted. All missiles neutralised by US and French warships so far were shot down by sophisticated shipborne surface-to-air missiles (SAM), proving that the modern vertical-launch systems guided by the latest generation phased array radars work as designed. Many nations earmarked to participate in OPG have ships with similar capabilities. Almost all also carry modern surface-to-surface missiles that can attack targets at sea or land. If the task of OPG were to be defined narrowly, only to prevent hits on merchant ships, it could be performed using the centuries-old principle of sailing in convoys with the protection of warships. In a convoy, slow, defenceless commercial cargos sail in several columns at precisely defined distances from each other — led, flanked and tailed by fast warships that can take on any threat. The system is effective, as the United Kingdom, Russia, Malta, and many other countries saved by convoys in World War II can attest. But every strategy has its limitations. A convoy is big and cumbersome, extending for miles to give behemoth ships a safe distance from each other and to enable them to manoeuvre if needed. Whatever the protective measures taken, huge tankers and container carriers – longer than 300 metres (984 feet) – still present big targets. Captains of commercial ships are generally not trained in convoy operations, and most have no experience operating in large groups or under military command. Their escorts, even if well-armed, carry a limited number of missiles and must plan their use carefully, allowing for further attacks down the shipping lane and ultimately leaving a war reserve for the defence of the ship itself. Once they expend some of the missiles, they need to replenish them – a task that is possible at sea but done much more quickly and safely in a friendly port out of reach of Houthi missiles. To clear the critical 250 nautical miles (463km) along the Yemeni coast leading to or from the Bab al-Mandeb strait, advancing at assumed 15 knots (28kmph) — as convoys always sail at the speed of the slowest units — ships would be exposed to even the shortest-ranged Houthi missiles and drones for at least 16 hours. And before even trying to make the dash, they would be particularly vulnerable in the staging areas in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden where ships would spend some time gathering, forming the convoy and setting under way. The Houthi missile threat is now known to be high, and their arsenal is substantial. Naval planners must be worried by their ability to mount concentrated prolonged attacks simultaneously from several directions. This was demonstrated in the very first attack, on October 19, when the Houthi launched four cruise missiles and 15 drones at USS Carney, a destroyer that is still operating in the Red Sea and will be part of OPG. The attack, probably planned to test the Houthis’ attack doctrine and enemy response, lasted nine hours, forcing the crew of the target ship to maintain full readiness and concentration for a prolonged period to intercept all incoming missiles. Every admiral would tell his political superiors that military necessity would call for attacks on Houthi missile infrastructure on the ground in Yemen: fixed and mobile launch sites, production and storage facilities, command centres and whatever little radar infrastructure there exists. A proactive response to the missile threat, in other words, to destroy the Houthi ship-targeting capability, rather than the reactive one limited to shooting missiles down as they come in. In theory, attacks against Houthi missile infrastructure could be based on satellite and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) reconnaissance and carried out by missiles launched from the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean and armed drones from distant land bases. But the only realistic chance at meaningful success would require the use of combat aircraft, bombers based on the two US Navy nuclear carriers in the region. Attacks against targets in Yemen would have a clear military justification. But they would also carry a clear political risk: that of the West, particularly the US, being seen in the Arab and Islamic world as actually entering the Gaza war on the side of Israel. After all, the Houthis say their attacks on Red Sea ships are aimed at getting Israel to end the war. Aware of the perils of such a development that could easily cause the conflict to spread, the US has tried to tread carefully, engaging with regional powers, and sending messages that it wants no escalation. It even openly demanded of its ally Israel that it limit civilian suffering and end

Chennai: One dead, several injured after Indian Oil plant boiler burst in Tondiarpet

Fire tenders are present at the spot. More details awaited.